Rooted in Resilience: Chuvash Plant Traditions

I wrote this article for VBKB, Vereniging van Botanische Kunstenaars België (Belgian Botanical Artists Society).

It was featured in the Society’s December 2025 newsletter.

The Chuvash are an Indigenous Turkic people of the Atăl (Volga) River region, considered to be descendants of semi-nomadic warrior tribes, the Huns. For centuries, long before Russia’s colonial practices reshaped the region, they have lived in harmony with nature, sustaining themselves through agriculture and animal husbandry. This close, spiritual relationship with the land is rooted in beliefs in which plants are not merely resources, but living beings and active participants in daily life, medicine, rituals, and culture. Today, this relationship with nature persists as a quiet form of cultural resilience, even as colonization, assimilation policies, and modernization fractured many traditional ways of life.

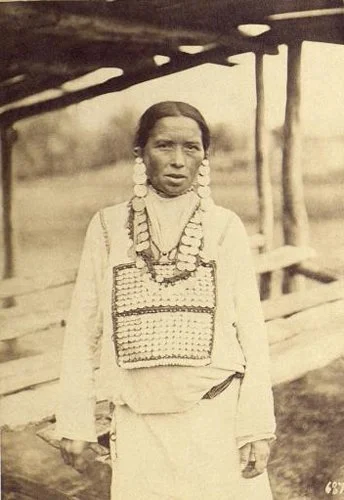

Stylized botanical imagery appears throughout Chuvash artistic traditions and crafts. While not “botanical art” in the scientific sense, these motifs act as an artistic representation of flora, expressing cultural identity and beliefs. Chuvash embroidery is filled with plant symbolism. Floral patterns, vines, and the ancient “Tree of Life” motif decorate clothing, ritual towels, and household textiles. Woodcarving and jewelry also feature stylized plants.

Botanical motifs in Chuvash embroidery, jewelry, and woodcarving tell a story of endurance. They are more than decoration. During periods when speaking Chuvash or practicing the traditional belief system was discouraged, these designs became a subtle yet powerful form of resistance. They allowed Chuvash people to preserve their identity in plain sight, stitching cultural memory into shirts, towels, belts, and ritual cloths that could be openly displayed even when their deeper significance had to be quietly protected.

Traditional Chuvash belief system blends animism and Tengrism, placing plants and trees at the heart of spiritual life. Birch, oak, and linden trees were considered sacred and were thought to house protective spirits. Villages often maintained sacred groves where communities gathered for prayers and seasonal rituals, leaving offerings to ensure harmony with the natural world. With Russian imperial expansion and the forceful spread of Orthodox Christian practices, many of these sacred spaces were destroyed or repurposed, and the ceremonies they hosted were labeled “pagan” and discouraged.

For example, the oak is a sacred tree linked to the Upper World and the sky god Tura, so oak groves served as holy spaces. Tura is associated with light, order, justice, and thunder. Because lightning often struck oaks, the tree was believed to be a bridge between the human and celestial worlds. Pre-colonial jewelry frequently featured acorn-shaped pendants of silver or gold, worn as talismans of protection and good fortune. Despite Christianization, the oak retained its sacred presence not only through folklore but also in rural customs, representing strength, protection, and divine power. Even now, images of acorns and oak leaves can still be found on house frames and gates, and some sacred oak groves continue to be maintained.

Other plant symbols carry equally deep roots. The lotus, symbolizing the sun and rebirth, appears on 17th–18th century tombstones and in jewelry worn by both men and women. Sunflowers and daisies on women’s jewelry, Syulgam, represented large, flourishing families. The rosebud symbolized purity, while the lily evoked spring’s awakening.

From left to right: an oak pendant, lotus, and a flax symbol depicted on Syulgam (a part of female clothing).

These symbolic plants are mirrored in seasonal practices and everyday life. Birch branches, grains, wheat, and herbs appear in festivals such as Kărlăç, welcoming of spring, and Akatuy, the agricultural celebration, where they signify renewal and prosperity. Beyond ritual use, Chuvash communities relied on extensive knowledge of local plants for healing and protection. Medicinal herbs like mint, yarrow, and St. John’s wort were used to treat illness, care for livestock, and perform seasonal purification. This knowledge was traditionally passed down within families: my Chuvash grandfather gathered plants and prepared his own herbal medicines.

Despite centuries of pressure, Chuvash plant traditions persist, and they are returning with new strength. Community groups are reviving seasonal rituals. Artists are reinterpreting botanical symbols. Young people are learning the meanings of their ancestors’ patterns. Herbal knowledge is being recorded, shared, and taught again. Each plant motif on cloth, each birch branch in a festival dance, each herbal remedy is an act of quiet defiance in the ongoing struggle to preserve and reclaim a culture that colonization tried, but failed, to erase.

This legacy is personal, too. I believe my ancestors’ relationship with nature was both precious and profound: a source of strength, identity, and balance. It’s no surprise, then, that plants became the heart of my own creative work. Botanical art feels like a continuation of that lineage: a way to honor the unity between people and the land, to celebrate the harmony my ancestors cherished, and to keep their connection to the natural world alive through every painted leaf and flower.